The battle of the Hurtgen Forest

The first American unit involved in the Hurtgen Forest battle was the 9th Infantry Division.

Early in the morning of September 14th, 1944, elements of the 9th Infantry Division, supported by the 746th Tank Battalion started their advance across the Belgian – German border at the villages of Roetgen and Monschau. Their mission was to penetrate the German Siegfried Line, also known as the West Wall, and seizing the road centers in the area between Monschau to the south and Duren to the north. Three days after the attack started, elements of the 47th Infantry Regiment completely penetrated the Siegfried Line, and captured the town of Schevenhutte. Meanwhile, the 39th Infantry Regiment fought their way through the first line of defenses near the town of Lammersdorf while the men of the 60th Infantry Regiment pushed through the line near Hofen. The first part of the attack looked successful. However, well organized German resistance halted the advance of the 9th Infantry Division men at these positions, and the fast advance that started in Normandy two months earlier, ended right there. Hard and brutal fighting for small objectives was about to start. The battle of the Hurtgen Forest had begun.

47th Infantry Regiment’s actions near Schevenhutte:

To accomplish the mission of breaching the West Wall defenses and capturing road centers between Monschau and Duren, the 9th Infantry Division commander ordered the 47th Infantry Regiment to proceed northeast from Roetgen along the western edge of the Hurtgen Forest. The regimental commander used his 3rd Battalion to protect the right flank by proceeding through the forest mass, while the bulk of his command followed the edge of the forest. German resistance to the advance was sporadic and disorganized. The third battalion executive officer, Major W. W. Tanner, stated that, from the time they had left Roetgen until reaching the town of Schevenhutte, they did not receive a single round of artillery or mortar fire, due in a large measure to the fact that the enemy did not know exactly where they were. Further evidence of this was the fact that every night some part of the enemy forces would blunder into the Battalion area, completely unaware of the presence of the American troops. The most serious threat during this three day advance was an engagement with the enemy on September 15th, when a battalion of German Infantry marched into the bivouac area of the 3rd Battalion just south east of the town of Zweifall. The situation was cleared up within five hours, and the 3rd Battalion continued to a position east of Vicht for the night. On the 16th of September 3rd Battalion proceeded to Schevenhutte in an approach march formation and prepared a coordinated attack on Gressenich for the next day. This attack was called off when the Germans counter attacked from the northwest, north, and east. The Germans continued almost daily counter attacks through the 22nd of September when their final effort made by two companies was repulsed. They continued to harass Schevenhutte with artillery and mortar fire for several weeks. While the 3rd Battalion proceeded on the right, the 1st and 2d Battalions advanced through Zweifall and Vicht to Mausbach and Krewinkel. Here again, opposition was sporadic until the final positions were reached on the 16th of September.The 2nd Battalion cleared Mausbach and Krewinkel on that date but was withdrawn south out of Krewinkel on the following day. The 1st battalion occupied Mausbach on 16th of September and was moved to a position in the edge of the forest just south of Gressenich to attack the town in conjunction with the 3rd Battalion on the following day. This attack was also called off. In these positions, troops of the 47th Infantry Regiment withstood counter attacks and artillery and mortar fire for many weeks. They were not relieved when other elements of the 9th Division retired from the Hurtgen Forest to Camp Elsenborn on the 28th of October 1944, and stayed in position under the command of other Divisions.

39th Infantry Regiment’s actions near Lammersdorf:

The 1st Battalion led the 39th Infantry Regiment through Roetgen and Lammersdorf on 14th of September 1944 with the intention of clearing the main road (road 399) through Germeter and Hurtgen to Duren. However, when opposition just north of Lammersdorf proved persistent, the bulk of the Battalion moved across country to Finkenbur and then doubled back down the road to clean it up north of Lammersdorf. Then 2nd Battalion, which had followed the 3d Battalion of the 47th Infantry Regiment east from Roetgen, turned south to establish a road block 1,000 yards southwest of Jagerhaus. Leaving Company G to man the road block, the rest of the battalion attacked south-west in conjunction with the lst Battalion to clear the area north of Lammersdorf. These operations were completed by 17th of September and meanwhile the 3rd Battalion had taken over the mission of proceeding from Lammersdorf to Rollesbroich and then go northeast to Duren. The 3rd Battalion managed to reach the eastern edge of Lammersdorf before determined opposition developed on the 14th of September. The following morning each of the three rifle companies was ordered to probe for weak spots in the enemy defenses. Company I was on the road which bypassed Rollesbroich to the west, Company K went through Rollesbroich and then northeast and Company L went south through Paustenbach and then northeast through Rollesbroich. Only Company L made progress, getting through Paustenbach and conducting an ineffectual attack on Hill 554. The hill was to consume the efforts of the Battalion for the next two weeks since it was stoutly defended and commanded the terrain over which the Battalion was ordered to pass. After two days of little progress, the Battalion planned a coordinated attack on Hill 554 for the 18th of September with Companies I and K attacking from the north and Company L from the west. This was unsuccessful and it was not until the 29th of September, when Company K and the battalion’s tank platoon swept around to attack from the east and southeast, that the hill was finally taken.

On the 18th of September meanwhile, the 2nd Battalion of 39th Infantry Regiment opened an attack to seize the high ground north and west of Rollesbroich. Two companies attacked east out of Lammersdorf and after five bitter days of fighting managed to get the westernmost end of the ridge. Company G, which had been manning the road block near Jagerhaus, captured that little community on 23rd of September 1944 and four days later moved south to attack the east end of the ridge. Companies F and G then cooperated to clear the ridge on September 28th but were so reduced in strength that they were pushed off two days later,The 1st Battalion had gone to a position southwest of Zweifall on the 18th to probe southeast toward Germeter. However, after reaching the road junction just west of Hurtgen on the Weisser Wehe Creek, they were recalled to Mausbach on September 22nd to help repel a counter attack against the 47th Infantry Regiment. On 26 September the st was committed near Jagerhaus on the left of the 2nd Battalion but moved only a short distance before being sent back to an assembly area west of Lammersdorf. On October 4th, all troops of the 39th Infantry Regiment were relieved in position by elements of the 4th Cavalry Group and moved to an assembly area southeast of Zweifall for an attack on Germeter and Vossenack in conjunction with the 60th Regiment.

9th Infantry Division men in the Hurtgen Forest.

60th Infantry Regiment’s actions near Monschau:

On the right flank of the 9th Infantry Division the 60th Infantry Regiment moved southeast out of Eupen to Monschau on September 14th, 1944. Task Force Buchanan, with the 1st Battalion of the 60th Regiment as a nucleus, moved south out of Eupen, turned right through Sourbrodt and Camp Elsenborn, and then proceeded north to Monschau. The two forces tied in on September 17th and then attempted to cleanup the high ground to the southeast, including Hofen and Alzen. They continued on this mission until relieved by troops of the 4th Cavalry Group, after which they moved north for the attack on Germeter.*1

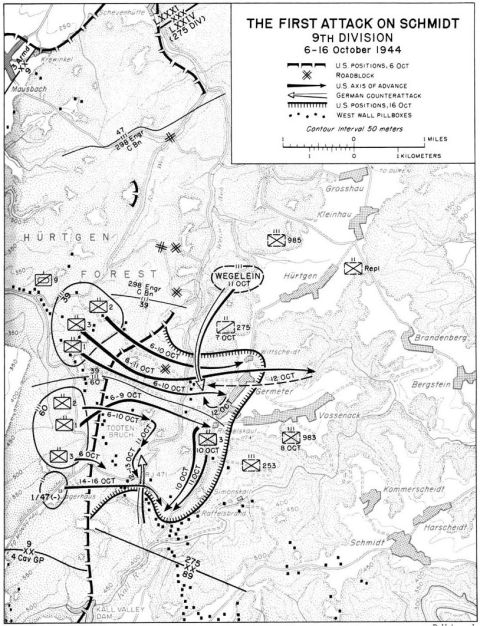

Map of the 9th Infantry Division’s October 1944 actions. Source: The Siegfried Line Campaign – US Army Green Book

The attack on Germeter and Vossenack:

The next effort of the 9th Infantry Division in the Hurtgen Forest was the coordinated attack of the 39th and 60th Infantry Regiments on the town of Germeter and the road centers to the southwest of that town. The plan was to have the 39th Regiment cut road 399 and take Germeter and continue to Vossenack while the 60th Regiment was to concentrate on seizing the road junction and high ground southwest of Germeter. The villages of Germeter and Vossenack, as well as the crossroads settlement of Richelskaul, were designated as the 9th infantry Division’s initial objectives. Lieutenant Colonel Van H. Bond’s 39th Infantry Regiment would attack on the left. Once it had occupied Germeter, the 39th Infantry Regiment would seize Vossenack while guarding against an enemy counterattack from the north. Meanwhile, after capturing Richelskaul, Colonel John G. Van Houten’s 60th Infantry Regiment would reorient itself to the south to guard against a German counter thrust from the direction of Monschau. The Division would then push on against the town of Schmidt. Jump-off time was originally set for October 5th but was later postponed for 24 hours.

The initial thrust would be conducted by four Battalions. The 39th Regiment used 3rd Battalion on the left and 1st Battalion on the right, with the 2nd Battalion following 3rd Battalion and protecting the north flank of the Regiment. The 60th Regiment used 1st Battalion on the left and 2nd Battalion on the right with its 3rd Battalion following the 2nd Battalion. In addition to support from two Regimental cannon companies, Major General Craig had four Divisional howitzer Battalions along with three Battalions of reinforcing artillery, for a grand total of 96 pieces. A company of 4.2-inch mortars was attached to each Regiment, along with a company each from supporting tank (746th) and tank destroyer (899th) Battalions.

Against this small force were the “Landsers” (German soldiers) of Major General Hans Schmidt’s 275th Infantry Division, which had briefly fought north of Aachen before being transferred to the Hurtgen in late September to fill a gap between the 12th Volksgrenadier Division and the 353rd Infantry Division. On October 1st, LXXIV Army Corps directed Schmidt to take over the entire Hurtgen sector, including the area occupied by the 353rd. As the 353rd’s headquarters and service units departed, its combat units were absorbed by the 275th. Schmidt also received the 353rd’s artillery component, giving him a total of 25 pieces, as well as six assault guns from Sturmgeschütz Brigade 902. Schmidt’s Division had originally consisted of a pair of grenadier (mechanized infantry) Regiments: GR 983 led by a Colonel Schmitz and GR 984 commanded by Colonel Joachim Heintz. Schmidt deployed Schmitz’s men in reserve while assigning the northern sector to Heintz. The center was allocated to one of the 353rd’s former units, Lt. Col. Friedrich Tröster’s GR 942, while the southern sector was the responsibility of Colonel Feind’s GR Replacement and Training Battalion 253. Feind commanded 1,000 men and was placed along the weakest portion of the line.

The attack starts

The Americans knew few of these details when they began their attack at 1000 hours on October 6th, 1944. Craig opened with fighter-bombers striking at otherwise invisible targets that U.S. Artillery units had marked with columns of red smoke. Once the planes departed, there was a five-minute preparatory Artillery barrage, then the U.S. foot soldiers began surging forward. Assaulting the extreme northern end of the line held by GR 253, the 1st and 3rd Battalions of Colonel Bond’s 39th Infantry Regiment gained 1000 yards while suffering 29 casualties. Lieutenant Colonel Oscar H. Thompson’s 1st Battalion attacked with A and B companies in the lead, trailed by C Company. Captain Jack Dunlap’s B Company drew first blood when it overran an outpost and killed or captured 30 men. Crossing a creek, Dunlap’s men pushed on until they encountered several pillboxes, whereupon he decided to hold up for the night. Thompson then brought his other companies on line and waited for daylight.

On the 1st Battalion’s northern flank, Lt. Col. Robert H. Stumpf‘s 3rd Battalion of the 39th Infantry advanced with L Company on the left and K Company on the right, with I Company in reserve. For the first 1,000 yards, the lead companies met only sniper and small-arms fire, but by late afternoon, heavier resistance had begun to build. Although L Company reduced an enemy strong point without too much delay, K Company was pinned down by accurate fire from a position southeast of the Battalion sector. As evening approached, Stumpf decided to hold in place until darkness to allow K Company to safely disengage. General Schmidt was sufficiently alarmed by American progress in this sector to order Captain Riedel’s Fusilier Battalion 275 to launch a counterattack against the Americans the next morning. Colonel Van Houten’s 60th Infantry attacked enemy defenses southwest of Richelskaul. On the left, Major Lawrence Decker’s 2nd Battalion moved forward 500 yards before its lead platoons were pinned down. Every attempt to advance ended in failure and heavy losses. By the time the attack petered out, 130 of Decker’s officers and men had become casualties.

To the right, Van Houten’s 3rd Battalion of the 60th soon encountered difficulties of its own. After a short eastward advance, the Battalion ran into a pillbox which, together with heavy mortar fire and a strong enemy response on the left flank, occupied the attention of two of Van Houten’s companies for the remainder of the day. By nightfall, however, K Company was able to move about 1,000 yards to the southeast. At 1600 hours, the colonel directed that his 1st Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Lee Chatfield, move north until it linked with the 39th Infantry. At daybreak Chatfield would launch an attack to the east in order to outflank the Germans, barring Decker’s advance.

Both sides were prepared to launch their own attacks at almost the same time. Fusilier Battalion 275 went forward only to encounter Americans who had been expecting some sort of reaction to their previous day’s advance. Captain Riedel was wounded and the survivors of his unit pinned down. Captain Dunlap took advantage of the situation by infiltrating GIs into the woods just west of Germeter, but Colonel Thompson would not let him enter the village for fear it would expose his B Company to counterattacking panzers. By noon the 1st Battalion had succeeded in bypassing II/GR 942. Schmidt reacted by deploying Landesschützen Battalion I/9 to the rear of II/GR 942. The American success also convinced him that “the southernmost elements of GR 253 defending a line of West Wall bunkers were thus in danger of being enveloped from the rear.” Schmidt ordered Colonel Feind to block off the threat of a further enemy penetration in that sector. In response, U.S. Engineer Battalions 16 and 275 occupied positions between Richelskaul and Raffelsbrand while three companies of Engineer Battalion 73 dug in along the Hurtgen-Germeter road.

During the night of October 7th to 8th, Colonel Schmitz sent reinforcements to the aid of GR 253. Fortress Infantry Battalion 1412 and Luftwaffe Fortress Battalion 5 were also dispatched by LXXIV Army Corps to reinforce the 275th. In addition Schmidt received two companies of civilian police from Düren, hurriedly issued with army uniforms and rifles. He combined the police into an ad hoc formation named Battalion Hennecke (after its commander). Several howitzer batteries from the 89th Infantry Division, an anti-aircraft artillery Regiment and elements of an artillery corps were ordered to occupy positions where they could augment the fire of Major Sturm’s Artillery Regiment 275. With fresh troops and additional artillery, Feind planned to launch a coordinated counter thrust at dawn, using I/GR 983 and Engineer Battalion 275. His intended target was Colonel Chatfield’s 1st Battalion, 60th Infantry, now located just west of Richelskaul. Advancing northwest from Simonskall, the German counterattack crumbled when it came under intense mortar, artillery and small-arms fire.

The 39th Infantry Regiment planned to renew its advance at 0800 hours on October 8th, but a heavy barrage began falling on its lead Battalions an hour before the attack was to begin. The 3rd Battalion suffered a serious setback when its L Company commander was killed and casualties disorganized his unit. Immediately following the barrage, a German force of 150 to 200 men counterattacked the 1st Battalion but was repelled by Captain Ralph Edgar’s A Company. The Germans then shifted their efforts farther north, hitting L and I companies. Colonel Bond sent G Company from the 2nd Battalion, which quickly overran three enemy machine guns. The loss of the automatic weapons seemed to take the fight out of the Germans, who retired to the east. Thirty German soldiers were killed during the engagement, and 27 others, including a wounded company commander, were captured. After thwarting the enemy counterattack, Bond ordered his lead elements to resume their advance at 1100 hours. Bolstered by the arrival of supporting tanks, L and I companies moved forward. By 1215 hours, L Company had gained 200 yards and captured three pillboxes. The 3rd Battalion’s progress slowed and finally came to a halt shortly before 1800 hours. Still lacking supporting tanks, Thompson’s 1st Battalion did not attempt to advance across the open ground surrounding Germeter.

The 1st Battalion, 60th Infantry, launched its own attack against the Richelskaul road junction at 1100 hours and was met by intense artillery and mortar fire. B Company, accompanied by several tanks, was able to detour north into the 39th’s zone of operations before veering back east again. This small force pushed to within sight of the crossroads before holding up for the night. The 2nd Battalion, however, was unsuccessful in overcoming the enemy to its front. Although the Germans had been pushed back, two days into the attack the Americans had yet to defeat the 275th, which continued to maintain an unbroken line of resistance. The bloodletting would continue. During the night, Van Houten made plans to push eastward now that supporting tanks and tank destroyers had linked with his leading elements. Led by a platoon of M4 Shermans from the 746th Tank Battalion, Van Houten’s 1st Battalion pushed out into open ground south of Germeter at daybreak.

The 39th joined the attack at 0700 hours, but without artillery preparation. This time, supporting tanks were available and actively engaged. The 1st Battalion made a short advance to the edge of the clearing surrounding Germeter before being brought to a halt. C Company suffered particularly heavy casualties when it attempted to breach a barbed wire entanglement. Only the tanks attached to B Company were in position to place effective fire on the enemy defenders. By 1900 hours, a platoon from C Company finally succeeded in working several men close enough to the outskirts of Germeter to begin exchanging hand grenades with the Germans. Unable to support them however, at nightfall Thompson ordered them to pull back.

The 3rd Battalion moved out 45 minutes behind the 1st. As it advanced, the sound of tracked vehicles could be heard near Wittscheidt, and for the rest of the afternoon occasional high-velocity rounds exploded in treetops throughout the Battalion’s sector. Despite enemy sniper fire, I Company was able to occupy Wittscheidt by 1615 hours. With darkness approaching, Colonel Stumpf decided to halt his advance. To forestall the possibility of an armored counterattack from the direction of Hurtgen, he directed I Company to mine the road leading to Wittscheidt and to register artillery on all likely enemy routes of approach.

Any plan to resume the advance the next day, October 9th, was forestalled by a dawn counterattack by Battalion Hennecke that overwhelmed two platoons from I Company, capturing 41 men. The German success meant that Bond would have to spend the rest of the day just trying to retake the ground he had lost. The 1st Battalion likewise did not attack as planned. Each time Thompson’s men tried to move forward they received accurate small-arms fire as well as direct fire from German self-propelled guns. Things went somewhat better for the 60th Infantry. The 1st Battalion pushed off at noon to seize the Raffelsbrand road junction south of Germeter. In what seemed to be a nightmarish repetition of the opening days of the attack, the thinned ranks of hungry and bone-weary GIs trudged forward while steadily losing men to incoming fire. The situation changed dramatically when one of the lead companies overcame a German pillbox covering the road between Reichelskaul and Raffelsbrand. Buoyed by success, the Americans pushed southward, collecting 100 prisoners and securing their objective by nightfall.

With Raffelsbrand in American hands on October 10th, Van Houten ordered the 3rd Battalion to redeploy to Richelskaul to protect Chatfield’s rear and maintain pressure on German units massing southeast of Germeter. The loss of the road junction persuaded Schmidt that he needed additional troops. LXXIV Army Corps agreed to loan two rifle companies from the 89th Infantry Division, provided they were used only along the threatened southern flank. The reinforcements would not arrive until dawn on October 11, however, and in the meantime Schmidt sent a company each from GR 983 and GR 984 to strengthen Colonel Feind’s GR 253.

The Americans’ position was also somewhat precarious. With no reserves available, Van Houten had nothing to send to Chatfield’s aid. To the east, the 2nd Battalion, 60th Infantry, was still being held back by the stubborn defenders of II/GR 942. To the north, the 39th Infantry remained stalled outside Wittscheidt and Germeter.

October 11th brought success and failure for both sides. American attempts to exploit success at Raffelsbrand produced nothing but longer casualty lists. A German counterattack struck Chatfield’s men before daylight, and though beaten back, Chatfield reported that “the enemy maintained pressure here for the rest of the day and crowned it before dark with a bayonet charge.” When the Americans tried to bring up reinforcements, they were pinned down by several pillboxes along the Richelskaul-Raffelsbrand road that they had bypassed the previous day. The 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry, was finally able to enter Germeter but found that its defenders had abandoned their positions during the night. Hoping to seize more ground, Thompson ordered Captain Edgar’s A Company, supported by Lieutenant Robert Sherwood’s 1st Platoon of C/746th Tank Battalion, to probe eastward toward Vossenack. The column had only covered 500 or so yards when a Panzerschreck knocked out the lead tank, and the remaining American armor and infantry withdrew. A subsequent advance by A Company under cover of smoke ended with the destruction of two more Shermans.

The Americans had some success to the north and west of Germeter. Leaving I Company behind to protect the northern approaches to the town, K and L companies encountered little resistance as they moved eastward from Wittscheidt. By late afternoon, Stumpf’s Battalion had advanced nearly a mile and was preparing to attack Vossenack from a ridge northeast of the village. The 2nd Battalion was also able to advance. Craig’s men had at least been gradually moving forward, but ominous events had occurred during the night that would soon threaten what little progress they had made. Accompanied by the LXXIV Corps commander, Lt. Gen. Erich Straube, Seventh Army commander Lt. Gen. Erich Brandenburger visited Schmidt’s command post. After hearing a candid assessment of the situation, Brandenburger promised to send Regiment Wegelein, a unit composed of well-trained and well-equipped troops to the front. Numbering 161 officers and 1,639 enlisted/officer cadets, the force was organized with three Battalions of three companies each and a Regimental heavy-weapons company. Its commander, Colonel Helmuth Wegelein, was an experienced leader. Schmidt and Wegelein quickly agreed that a counterattack against the northern flank of the Americans had the best chance of producing favorable results. Wegelein would launch his assault from an assembly area near Hürtgen, advancing southwest until he isolated the American Battalions near Germeter.

Following a brief but concentrated artillery preparation, Wegelein’s men advanced from their positions just before dawn, moving purposefully along the wooded plateau paralleling the Germeter-Hurtgen road. A platoon of dismounted armor crewmen from 746th Tank Battalion, securing a roadblock along the left flank of 2nd Battalion, 39th Infantry, was the first to encounter this new threat and was quickly scattered. By 0700 hours on October 12th, Wegelein had succeeded in isolating several of Lt. Col. Gunn’s rifle companies. As testament to the isolation caused by the densely wooded terrain, the 39th’s 3rd Battalion was completely unaware that the nearby 1st Battalion was being cut to pieces. Lacking reserves to blunt the enemy thrust, Colonel Bond requested help from General Craig, who directed elements of the Divisional reconnaissance troop ( augmented by a platoon of light tank) to assist the embattled 39th Infantry. As the situation grew more serious, Craig ordered the 47th Infantry at Schevenhutte to dispatch two rifle companies and a company of medium tanks from the 3rd Armored Division to reinforce Bond. Rushed to the point of greatest crisis, these reinforcements were finally able to halt the German advance when it reached the road leading west out of Germeter.

The abortive counterattack cost the Germans nearly 500 casualties, with little to show in return. The failed operation, however, produced at least one positive result for the Germans: Surprised by the strength and intensity of their assault, Bond ordered Stumpf’s Battalion to abandon its plans to attack Vossenack in order to reduce the salient Wegelein had created. Schmidt planned on renewing the counterattack on October 13th, but orders from LXXIV Army Corps directed the immediate removal of all officer candidates from the combat zone, which cut in half what remained of Wegelein’s unit and forced him to spend badly needed time reorganizing his remaining personnel. While he was doing so, the 3rd Battalion, 39th Infantry, launched an attack of its own against Wegelein’s troops. K Company led the effort, trailed by L Company. As the latter moved up on line, both of its leading platoons were ambushed and wiped out. K Company maneuvered to attack the enemy facing L Company while the 1st Battalion sent B and C companies into the fight. Another counterattack inflicted heavy losses on the right platoon of Dunlap’s company, but the American advance continued. At 1730 hours, a German bearing a white flag approached B Company and requested a brief cease-fire while his unit prepared to surrender. Dunlap sent the man back with a message that he would hold his fire for five minutes. When the German emissary did not reappear within the stated time, B Company resumed its advance, only to run into a torrent of small-arms fire. It was now almost dark, and the enemy seemed to be on all sides. Fearing that his exhausted company was losing its cohesion, Dunlap ordered his men to fall back a short distance and dig in.

Facing four enemy Battalions at Raffelsbrand, the 1st Battalion, 60th Infantry, was experiencing its own difficulties. Just before dawn, a surprise German attack seized a pillbox occupied by C Company. Although the seven GIs inside were able to escape, a counterattack by 30 men was unable to regain the position. Three Sherman tanks and two infantry companies eventually arrived to lend a hand, but even with those reinforcements, a heavy crossfire from several machine guns prevented the Americans from making any progress. One of the tanks was hit by an antitank rocket that wounded several men and forced the crew to evacuate the vehicle. A daring German soldier then ran out to the tank and drove it behind a nearby pillbox before the Americans could react. With this, the Americans lost all momentum, and at 1730 hours they began to fall back, suffering heavy casualties from enemy artillery and mortar fire.

That evening Wegelein went to Schmidt’s headquarters to protest orders for a renewed advance on the morning of October 14th, stating that communications to his Battalions and companies were so poor there was a risk that all units might not receive a Regimental order. Schmidt replied that he would accuse Wegelein of cowardice if he did not resume his attacks. Determined to show that he was no coward, Wegelein spent a busy night personally delivering the orders to his units. He still had more visits to make as the sun rose on the 14th. At 0800 hours, however, the colonel was shot and killed by the radio man of Kenneth Hill, both serving in the 39th Infantry Regiment, and his Regimental adjutant was captured moments later.

The fighting sputtered on and off for two more days, but it was clear that both sides were too exhausted to achieve significant results. At a cost of 4581 casualties, the Americans succeeded in pushing their front line an average of 3000 yards to the east. Non-battle losses (sickness, injury, trench foot, mental problems) for American units totaled nearly 1,000. The toll for the defenders was also high — approximately 2,000 killed or wounded and 1,308 prisoners.

After breaking off the offensive, General Collins made the questionable claim that the sacrifices of Craig’s men had drawn off German units that could have been thrown into the battle for Aachen. Although it is true that 19 German infantry and engineer Battalions opposed six American infantry Battalions, many of the defending units were much smaller than their counterparts. In any case, though the Hurtgen fighting might have prevented some German units from being sent to Aachen, their redeployment would not have altered that city’s eventual fate.

More important, given the experience of the 9th Infantry Division during the opening phase of the battle, the larger question is why senior American leaders such as Generals Courtney Hodges, Omar Bradley and Dwight D. Eisenhower chose in November 1944 to send Division after Division into the dark and foreboding woods right until the start of the German Ardennes offensive that December. By the time major combat operations in the area finally ceased, six U.S. Divisions had been fed into the meat grinder and some 33000 soldiers had become casualties without achieving a far push into Germany. Source: Armor in the Hurtgen Forest Report

According to the U.S. Army’s official history, “The real winner appeared to be the vast, undulating blackish-green sea that virtually negated American superiority in air, artillery, and armor to reduce warfare to its lowest common denominator.” Given the terrible cost, it seems clear that Major General James Gavin might have been more correct when he said: “For us, the Hurtgen was one of the most costly, most unproductive, and most ill-advised battles that our army has ever fought.“*2

*1 Source: Armor in the Hurtgen Forest Report

*2 Source: Parts of this article originally appeared in the December 2006 issue of World War II Magazine, ©2012 Weider History Group, and is posted here with permission from the publisher”.