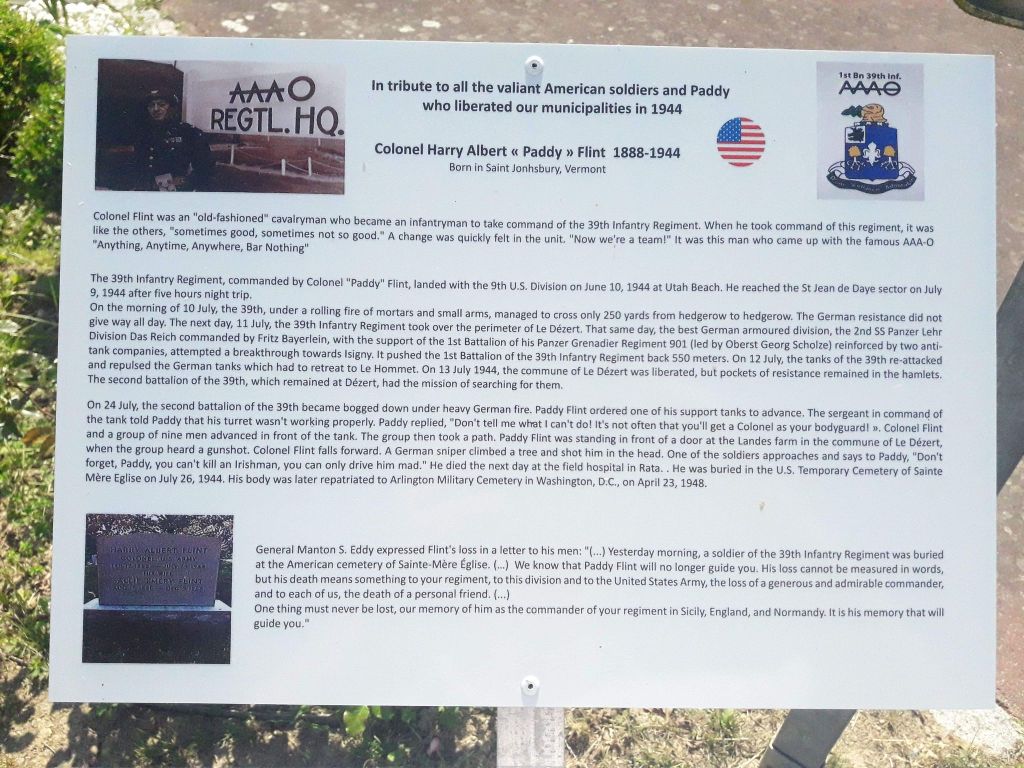

Colonel Harry Albert “Paddy” Flint

“Anything, Anywhere, Anytime, Bar Nothing!”

39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division

Soon the 39th Infantry Regiment had a mission: Securing the northern coast of Africa and thereby safeguarding the Mediterranean link in the Allied lifeline to the Middle and Far East. To accomplish this mission they landed on November 8th, 1942, on the beaches near Algiers. Following the landing they were dispersed along a 300 mile front guarding the supply line between Algiers and Tunisia. The 39th Infantry took a decidedly more active role in the war when they were deployed east of the famed “Kasserine Pass” as a covering force for the 1st Armored Division. This was followed quickly by successive battles in the final drive to Bizerte. The Regiment played a leading role in this action and brought the German Panzer Armee – Afrika to its knees and won control of North Africa.

The next battle campaign was in Sicily. Allied forces hit the Southern beaches of Sicily early in the morning of July 10th, 1943. Though the initial sweep placed 80.000 troops ashore, the fighting soon became a series of small engagements by artillery and infantry men. On July 17th 1943, the 39th Combat Team, joined by the 34th Field Artillery Battalion, joined the 82nd Airborne Division in a thrust north of the beaches. The 39th Combat Team captured 327 prisoners near Agrigento, thrusting forward through town after town. Lt. Colonel Van H. Bond led the 3rd Battalion across the Belice River into Castelvetrano on the 21st. This enabled the 2nd Armored Division on the right to attack north and capture the city of Palermo.

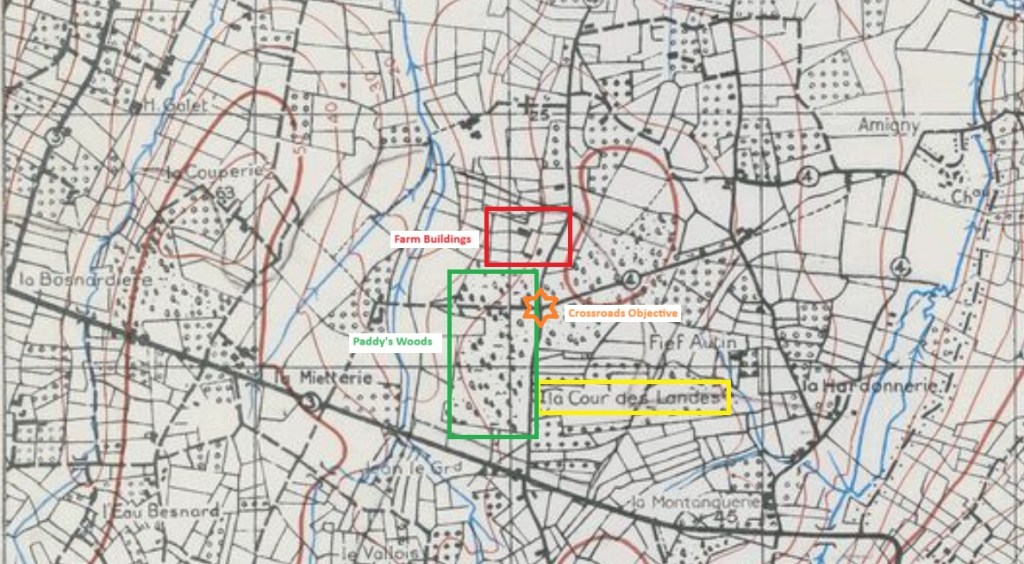

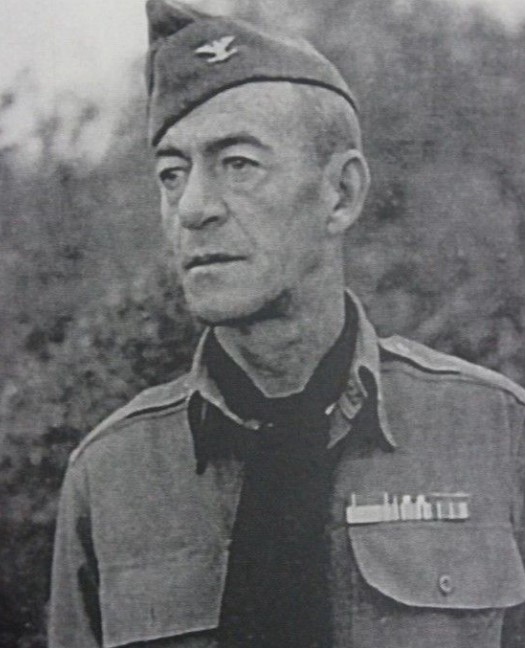

The 39th Regimental commander had to be evacuated after breaking his leg in an accident. The division commander, Major General Manton S. Eddy requested a new commander for the 39th Infantry and General Bradley recommended Flint, and Eddy accepted. In mid-July 1943, Flint was appointed to command the 39th Infantry Regiment while fighting was still ongoing in Sicily. Flint took immediate steps to restore the regiment’s morale and fighting spirit. He gained notoriety for some activities, with Lieutenant General George S. Patton, commander of the American Seventh Army (which controlled all American ground forces for the campaign), commenting at one point that “Paddy Flint is clearly nuts, but he fights well.” In a letter to his wife Beatrice, written on June 17, 1944, Patton wrote, prophetically: “Paddy is in and took a town. He expects to be killed and probably will be.”

AAA-O – Anything, Anytime, Anywhere, bar nothing!

The tale of how Colonel Harry “Paddy” Flint named his beloved 39th Infantry Regiment has several versions. The version that has been verified by several members of the 9th Infantry Division, and probably most true to the events as they happened, is that after Colonel Harry “Paddy” Flint assumed command of the Regiment in Sicily (back then it still was a Combat Team), he called his three Battalion commanders in for a meeting. He told them he was new to an infantry outfit and would need a little time to catch on to everything that should be done. Colonel Paddy had only one change in mind: “From now on” , he said, “we’re all going to work and stick together as a gang and help each other. I have a motto, you might not like it, but it is my motto, and it will be your motto too!” he continued. “Anything, Anytime, Anywhere, bar none!” he said with a loud voice. Colonel Paddy then soon after had a painter sit in view of his men, painting the “AAA-O” logo on his helmet and jeep. This would attract the attention of the men, and since Colonel Paddy had the painter stay there, anyone who wanted could also get the slogan painted on the side of their helmets. The idea caught on, and more and more men had the slogan painted on their helmet. After the Battalion commanders suggested that either no one had the slogan on their helmets, or everyone, it persuaded Colonel Paddy to issue an order, making the “AAA-O” slogan part of the 39th Infantry Regimental uniform.

“The Fighting Falcons“

The Distinctive Unit Insignia for the 39th Infantry Regiment depicted a Falcon.

It’s motto emblazoned the pin with the motto “D’une Vaillance Admirable” (with a Military courage worthy of admiration).

This insignia gave the regiment the nickname “The Fighting Falcons”.

Normandy, France 1944

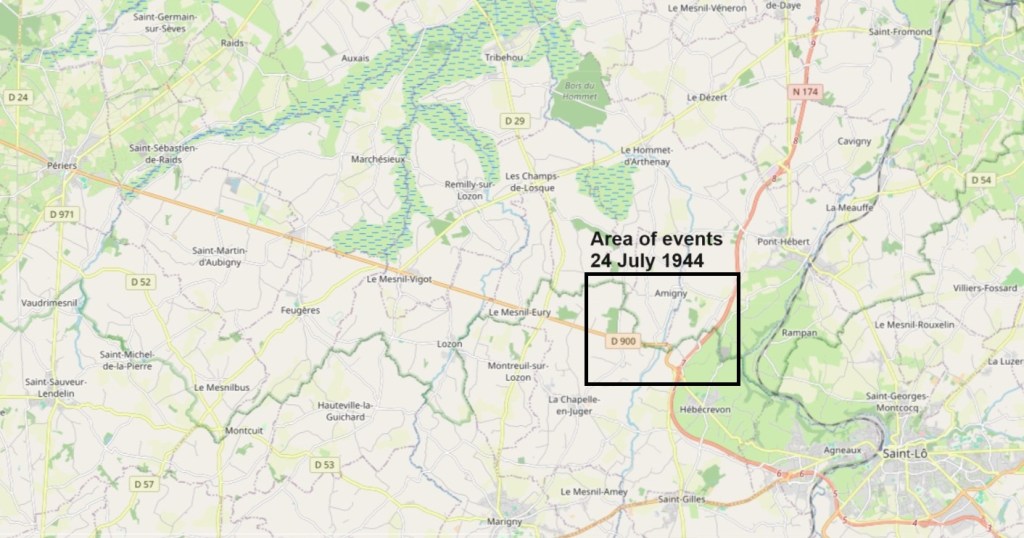

On July 2nd 1944 the 39th Infantry Regiment completed the mopping up operations on the remainder of the peninsula northwest of Cherbourg and it moved to a semi-rest area located near Les Pieux. A week later on the 9th of July, the regiment moved from its rest area 2,5 miles southwest of Les Pieux to an area 2 miles southwest of Carentan. Then on July 10th the regiment went into action in the vicinity of St.Jean-de-Daye with the 1st Battalion taking up a position 5 miles southeast of Carentan. The 2nd Battalion was just outside of St. Jean-de-Daye and the 3rd Battalion went into reserve. While most of the regiment was involved in bitter fighting around this town, parts were on flanking marches between 11 and 17 July. Movement was very slow since progress was from hedgerow to hedgerow over flat, easily observed terrain. On the 18th the regiment swung over to the vicinity of Esglandes by foot over secondary roads under heavy enemy artillery, mortar and small arms fire. Approaching the bigger city of St. Lo the regiment attacked and held positions in the vicinity from 18 to 24th of July. On this day, the 1st Battalion took up positions near La Chapelle, the 2nd Battalion near Les Gives and the 3rd Battalion near the town of Marigny.

It was on this day, July 24th, 1944, that Paddy’s good ol’ Irish luck ran out.

A large-scale air bombardment on German positions along the Périers – Saint Lô road was planned to open the US First Army advance, code named Operation Cobra on the 24th of July, 1944. The breakthrough was designed to create a wide gap in the German defensive line. The plan was to have 1581 bombers and 500 fighters support the advance and to bomb the VII Corps area in the Marigny – Saint-Gilles region, just west of Saint Lo. Once a breakthrough had been created, the First Army would then be able to advance into Brittany, rolling up the German flanks once free of the constraints of the bocage country. The attack was initially scheduled for the 24th but was called off due to bad weather conditions and was to take place the next day on July 25th.

On July 24th 1944, the 9th Infantry Division was advised that this bombardment by the 8th and 9th Air Force would take place and was to start at 13:00 hours. For safety reasons, the troops in the target area were withdrawn.

The 8th Infantry Regiment moved forward on the left at 13:00, after the bombing was called off because of poor visibility. Then the 2nd battalion of the 39th Infantry Regiment reoccupied former positions and continued pressure while the 3rd Battalion moved east of La Cour des Landes and swung to the west in flanking movement on canters of resistance. 2nd Battalion moved on the left flank forward and secured a Command Post (at 4214711) and 3rd Battalion worked its way forward after small arms resistance was no longer a threat and established contact. During this attack, Colonel H. A. Flint attempted to move the right flank company of the 2nd Battalion forward by infiltration. We will take a closer look at the events that followed.

The events near La Cour des Landes, 24 July 1944

Throughout the 24th day of July 1944, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 39th Infantry Regiment were engaged in several fights with the German opposition who were well entrenched in the area 300 to 500 yards north of the Périers – St. Lo road. Progress was slow, and only small gains were realized up to noon. The 3rd Battalion moved east of La Cour des Landes and swung to the west in a flanking movement to assist the 2nd Battalion facing gun emplacements and in knocking out a center of resistance located in the woods that were threatening the nearby crossroad.

Anti-Tank guns and automatic weapons located in this center of resistance had prevented further movement to the south and had held up the line of advance to the main road to the south. After many attempts made by the 2nd Battalion’s men, the 3rd attacked the gun positions supported by “F” Company. At around 1515 hours Paddy reported by radio to 2nd Battalion HQ that he was going to take several Tank Destroyers and have them support F Company, the company he was with at that moment as well.

We will see a series of Radio Messages. In these messages, the Radio Call sign N-6 is the sign for Colonel Flint.

White is the Radio Call Sign for 2nd Battalion, and the Radio Call Sign N-5 is Lt. Col. Van H. Bond.

After receiving several radio messages coming from both 2nd and 3rd Battalion, Paddy visited the Command Post around 15:00 in the afternoon.

Paddy was known to wear a black handkerchief around his neck. When one of his fellow officers asked about it, he grinned and said “It’s the pirate in me!”

The Regimental S-3 Major Thomas A. E. Mosely was there as well, alongside Paddy’s radio / walkie talkie operator Tech Sergeant Harold M. Bruskin and his jeep driver Tec 5 Charles E Witzel. Hearing that heavy enemy concentrations of frontal and flanking fire was being zeroed in on a small orchard surrounded by hedgerows some 500 yards north of the important St. Lo / Marigny – Periers road, preventing his men from advancing, Paddy knew he had to do something. He also noticed that 2nd Battalion Commander Lt. Col. Frank Gunn was not present at the Command Post. Before heading off to find Lt. Col. Gunn, Paddy observed the surroundings to get a good tactical understanding of the situation.

He noticed stiff German resistance coming from a small cluster of about 3, maybe 4 farm buildings in the area. The house was settled into an orchard amongst several hedgerows and was located alongside the present D-189 road. Besides the enemy resistance at this location, heavier shells were also fired onto his leading men. It was soon discovered that the heavier fire was coming from four or six marauding tanks that had moved up on the road north from the crossroads. Not meeting any American resistance, they just advanced up the road near the vicinity of the farm buildings and were firing one shell after another onto the advancing men of the 39th Infantry Regiment.

Armed with two carbines and a M1 Garand rifle Paddy started his advance through the nearby thick 18 inch high grass, dodging incoming rounds and bullets as he moved forward. He then quickly located F Company and found Lt. Col. Gunn. Observing the situation again, he noticed the Germans had put up their defense positions in and around the farm buildings. Paddy sent a radio message to the 2nd Battalion HQ Commander Van H. Bond, back at the Command Post, that he was going to take several Tank Destroyers and have them support F Company,

15:18 hours: N-6 at White: Moving T.D. forward to crush the house. Am with F Company”.

While observing the area, they also discovered a pillbox, and Tech Sergeant Bruskin shared the following message through the radio:

16:00 hours: “From N-6 to N-5: Strangely quiet here. Could take a nap . Have spotted pillbox, will start them cooking!”.

“Quiet” might have been a word to use by Paddy to downplay the danger in the area. Right at that moment, an enemy soldier had craftily worked his way through the heavy shrub growth and popped up on the same side of the hedgerow as Colonel Flint and his men. The German immediately opened fire and sprayed several bursts into Paddy’s direction. This event was later described by Brigade General Frank Gunn.

“About 5 or 10 minutes before Paddy was wounded, he visited me as I was in the area of one of my assault companies (Company F/39). I wanted to see what help I could get them in order to move ahead. Paddy got on a hedgerow to get a better look, and then the Germans fired small arms at him! Several bullets clipped his trousers. When I told him to take cover he said “hit don’t make no difference. They can’t hit a damn thing anyway!”. He did however get off the hedgerow and moved from my area to another unit on our right, where he eventually got hit”.

By now, one platoon of tanks, Tanks, Tank Destroyers and Engineers had been attached to Paddy’s 2nd Battalion. Paddy noticed a Sherman tank nearby, just sitting there idle. Paddy left the F Company area and marched his way over to the tank, that was just standing there, not doing much to support making the advance a success. Paddy demanded the tank commander’s attention and ordered him forward to clear the enemy from the road so that Gunn’s 2nd Battalion could advance. The tanker responded that the turret was not working right. Angry at the tank commander Paddy fumed back in reply “Don’t tell me what you cannot do…it isn’t often that you have a Colonel as a bodyguard!” These words made the tank commander move into action, and the Sherman tank finally moved forward.

Now with G Company, Paddy took 4 riflemen along, moved out out and took the road behind the mind clearing Engineers that were paving the path for the Sherman. Paddy and his men were behind, alongside or sometimes in front of the tank, always pushing to gain ground and head towards the crossroads just about 500 yards to the south, not too far from the farm buildings that were giving them a strong opposition. Again Paddy had a radio message delivered to Lt. Col. Van H. Bond.

16:35 hours: “From N-6 to N-5: We are kicking loose from here, too. Using tanks as Germans use them”.

Right then, enemy fired rained down on the Engineer Sergeant who was out in front of the tank digging up mines to clear the path for the Sherman. The tank reacted quickly and also opened up fire and methodically hosed down the hedgerows and the woods framing both sides of the road. It did not take much fire before seeing the German troops leaving the group of small buildings ahead of them, pulling back to the hedgerow line just south of the farthest building.

Seeing the enemy fall back, Paddy ordered the tank to pull up at the edge of the road. Then he climbed the turret to shout more instructions to the driver and crew, not caring anything about the fact he was fully exposed as a target now. An instant hail of fire rained down on Paddy and the tank. Miraculously they all missed him, but did clip the Sherman’s portable antenna, ricocheted off the armor plating and then grazed the leg of Tech Sergeant Bruskin, the Colonel’s radio operator.

Finally Paddy jumped down from the tank to get into a more covered position. He shouted more instructions to the tank driver, ordering him to move the tank another 50 yards down the road. This would give Paddy and his men enough time to make a flanking movement around the buildings. They arrived at the farm buildings and another radio message was sent back to HQ.

17:13 hours: From N-6 to N-5: Am at 3 houses – Pushing on with tanks

After a quick check of the houses, Paddy moved on.

17:16 hours: From N-6 to N-5: Have tanks come down hedgerow

Moving out far in front of the leading troops of his regimental assault group, he started following a lane that separated the group of buildings from the next hedgerows and then crossed an open grassy area that led down to the next line of hedgerows. While he was moving, the Germans were shooting back up the hedgerows, rounds cracking overhead, snapping tree branches and kicking up dirt from Paddy’s path as his little group cut across the grassy pasture.

As he kept running forward, he did not even stop when his Jeep Driver, Tec 5 Charles Witzel, got hit in the right arm. Major Mosely stopped to bandage Wizel and take care of him. Mosely then also managed to silence a harassing German machine gun pistol nearby by throwing a hand grenade into that position.

Realizing that Paddy did not want to come back with him to the buildings, Moseley took the wounded Witzel and got him down to the safety of the nearby buildings. He then went back after Paddy, trying to convince him to also get back to the buildings. Soon he found Paddy again, firing like a madman onto the German forces. Mosely tried several times to convince Paddy to fall back to the buildings, and it took a couple of minutes before he finally gave in, and both men started to move back to the buildings.

It was now around 17_30 hours. Catching his breath, Paddy stood in front of the doorway of one of the buildings and discussed with a G Company Sergeant on how to best position the men while also pushing the German defenders back from the main regimental objective, the crossroads. Suddenly, a loud crack could be heard, and Paddy stopped talking mid sentence as his body slumped forward and fell to the ground. A German bullet had struck into Paddy’s head from the back.

What happened was that a nearby German sniper had crawled up a tree, found a good spot, and aimed his rifle at the soldier wearing the Colonel insignia on his uniform and helmet.

The following radio message arrived at the 2nd Bn HQ

17:30 hours: N-6 Injured – being evacuated – Take cover

17:55 hours: From Nudge 5 to Notorious 6: Reported Nudge 6 had been hit. Shot through top of the head – bullet went through helmet. Notorious 6 directed Nudge 5 assume command.

Soon, a medic came up to help Paddy.

Private Richard B. Kann was a Medic with the 39th Infantry Regiment and in the La Cour des Landes area. Learning that a man lay seriously wounded in the forward area, Pvt Kann voluntarily exposed himself to the intense enemy artillery, mortar, machine gun, and small arms fire to go to the aid of the wounded man. As he was coming across the open clearing, he was ordered back to bring up a litter team, the wounded man having already been treated. This necessitated his movement to the rear, again under heavy enemy fire. As he started his return trip, he learned that the Regimental Commander, Colonel Flint, had been seriously wounded. Without hesitation, Pvt. Kann retraced his steps for the third time, across the open area and administered first aid to the wounded officer. For these actions, Private Kann was later awarded the Bronze Star Medal.

Before the aidmen took him away, Tech Sergeant Harold M. Bruskin, Paddy’s radioman, kneeled down next to Paddy and said: “Remember, Paddy, you can’t kill an Irishman, you can only make him mad.” The colonel smiled and was taken away on a stretcher by the medics.

After several unsuccessful attempts to knock out the German positions, F Company, with the assistance of 3rd Battalion, was able to oust the Germans from the strongpoint in the evening around 20:30. F Company kept this position during the night. It was a sad day for the 39th Infantry Regiment.

Colonel Harry A. Flint, “Paddy”, loved by the 39th Infantry Regiment and all through the ranks of the 9th Infantry Division, would eventually die of his wounds the next day, July 25th 1944.

Distinguished Service Cross

For the actions on July 24th, 1944, Colonel Flint was Posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Division: 9th Infantry Division

General Orders: Headquarters, First U.S. Army, General Orders No. 75 (1944)

Distinguished Service Cross Citation:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress July 9, 1918, takes pride in presenting a Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster in lieu of a Second Award of the Distinguished Service Cross (Posthumously) to Colonel (Cavalry) Harry Albert Flint (ASN: 0-3377), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving as Commanding Officer, 39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division, in action against enemy forces during the invasion of Normandy, France, on 24 July 1944. While advancing on the Saint-Lô-Périers road, Colonel Flint’s regiment was held up by heavy mortar fire. Leading from the front, Colonel Fling and a rifle patrol soon found the source of enemy fire. He reported by radio over the walkie-talkie: “Have spotted pillbox. Will start them cooking.” Calling for a tank, he rode atop it in a rain of fire as it sprayed the hedgerows. During the attack, the tank driver was wounded, stopping it, whereupon Colonel Flint crawled down, and went forward on foot with his men. As he led the patrol into the shelter of a farmhouse he was hit by a sniper’s bullet. He died of his wounds the following day. Colonel Flint’s outstanding leadership, personal bravery and zealous devotion to duty at the cost of his life, exemplify the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, the 9th Infantry Division, and the United States Army.

Colonel Harry A. Flint’s Dead and Burial

The news about Paddy’s dead got passed on by the men on the battlefield.

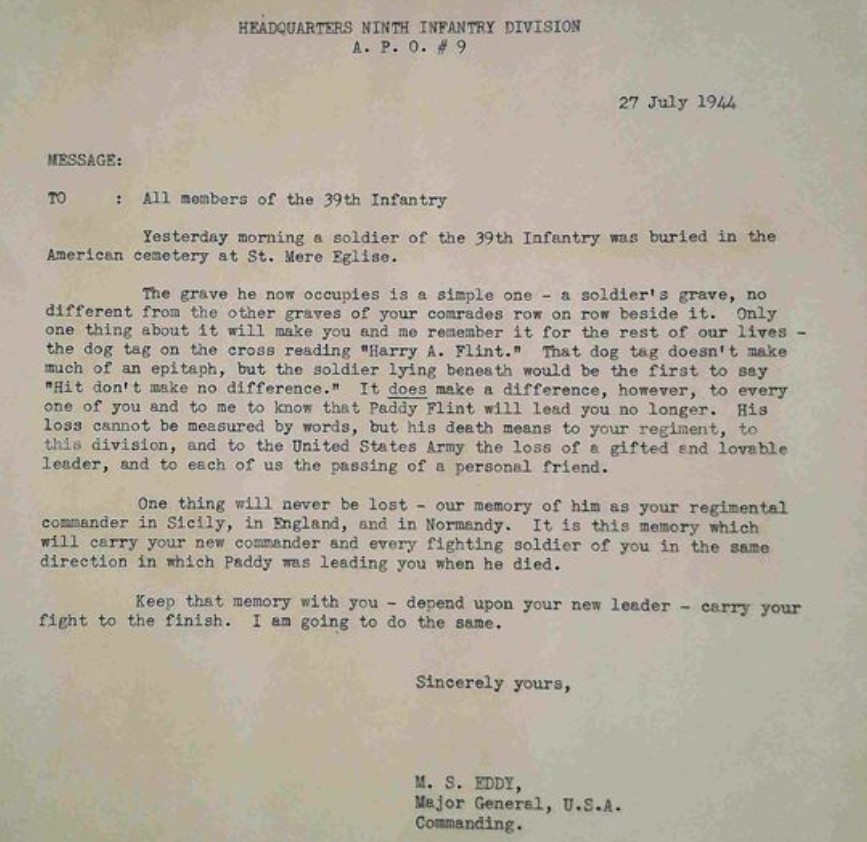

The day after Paddy died of his wounds, he was buried at the temporary cemetery in Sainte-Mère-Eglise.

On July 27th, the day after the funeral, Major General Manton S. Eddy issued a letter to the men of the 39th Infantry Regiment that read:

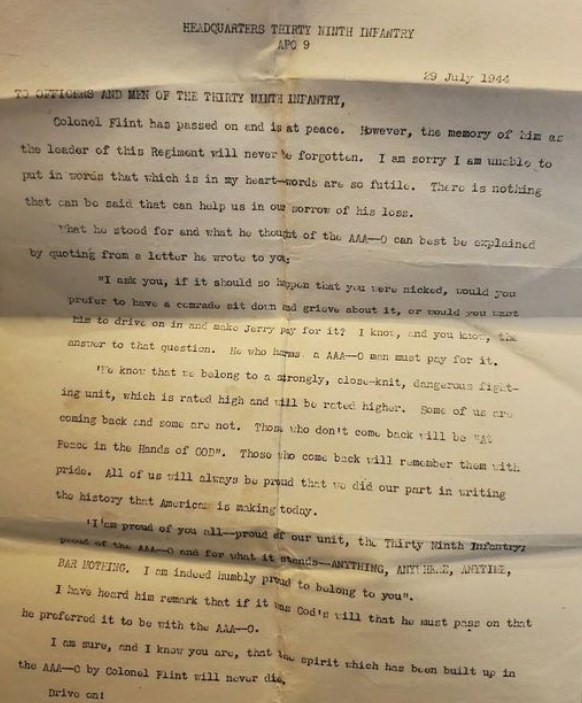

Another message was passed on to the men of the 39th Infantry Regiment on 29th July 1944:

HQ 39th IR, APO 9, 29 July 1944:

“TO OFFICERS AND MEN OF THE 39TH IR,

Colonel Flint has passed on and is at peace. However, the memory of him as the leader of this regiment will never be forgotten. I am sorry I am unable to put in words that which is in my heart – words are so futile. There is nothing that can be said that can help us in our sorrow of his loss.

What he stood for and what he thought of the AAAO can be explained by quoting from a letter he wrote to you:

“I ask you, if it should so happen that you were nicked, would you prefer to have a comrade sit down and grieve about it, or would you want him to drive on in and make Jerry pay for it? I known and you know, the answer to that question. He who harms a AAAO man must pay for it. We know that we belong to a strong, close-knit, dangerous fighting unit, which is rated high and will be rated higher. Some of us are coming back and some are not. Those who don’t come back will remember them with pride. All of us will always be proud that we did our part in writing the history that Americans are making today. I am proud of you all, proud of our unit, the 39th IR, proud of the AAAO and for what it stands; Anything, Anywhere, Anytime, Bar Nothing. I am indeed humbly proud to belong to you”.

I have heard him remark that if it was God’s will that he must pass on that he preferred it to be with the AAAO. I am sure, and I know you are, that the spirit which has been built up in the AAAO by Colonel Flint will never die.

Drive on!”

Re-burial at Arlington National Cemetery

It was on Monday afternoon, September 13th, 1948 that one of the greatest soldiers of World War II reached his final resting place at the Arlington National Cemetery. Located on a knoll, surrounded by large shade trees and overlooking the Nation’s Capitol, Colonel Harry “Paddy” Flint was laid to rest.

Members of the Ninth Infantry Division Association that attended the burial ceremony included:

Major General Louis A. Craig

Major General Donald A. Stroh

Brigade General George W. Smythe

Colonel John G. Van Houten

Colonel Van H. Bond

Lt. Colonel George E. Pickett

Lt. Colonel Fred C. Feil

Major Walter O. Beets

Donald M. Clarke

William L. Peverill

Frank B. Wade

Charles O. Tingley

Salvatore Trapini

William E. Byrness

Stephen Grey

Anthony B. Micke

Also attending were Mr. and Mrs. Beall, whose son, Captain John P. Beall, was Killed in Action while commanding Company D of the 39th Infantry Regiment.

Paddy had a great troop of honorary pallbearers:

Lt. General Haislip

Lt. General Chamberlin

Major General Drake

Major General Kirk

Major General Crawford

Major General Spaulding

Major General Maxwell

Major General Maloney

Major General Hayes

Colonel Thomas

Colonel Nalle

Colonel Van H. Bond

Lt. Colonel Clifton F. Von Kann.

Surrounded by the men who fought alongside of Paddy, men who respected their extraordinary leader, Paddy was laid to rest.

The Fighting Falcon had finally found a place to rest in peace.

Memorial plaques in Normandy.

While it is great that Colonel Flint has been commemorated in Normandy by several plaques, the information and location of the plaques are sadly not correct.

A plaque in the small town of Le Dézert claims that Paddy died because of wounds received in their small village, at a different farm.

A plaque was also put up a long time ago, stating:

Text engraved:

En Hommage au Colonel Flint

Tue au Dezert Le 25-7-1944

Et a ses hommes

Morts pour liberer le Canton

Translated in English to:

In tribute of Colonel Flint

Died in Le Dezert on 25 July 1944

And to his men

Who died to liberate the Canton

This plaque recently was moved and placed on top of another monument.

Colonel Harry A. “Paddy” Flint will forever be remembered .

This page will get more updates in the near future as we discover more facts and eyewitness reports.

Most of this information is based on official archival unit records, journals, reports, eye witness accounts,

newspaper clippings, articles and from various Ninth Infantry Division Octofoil Newsletters.

Thank you to Clément Fe for additional information on the actions.